The park proposals below are urgently needed to protect rare remnants of ancient Inland Temperate Rainforest. This type of rainforest occurs nowhere else in the world but in the province of British Columbia (BC), Canada. Most of it occurs in southeastern BC, in a mountainous region known as the Interior Wetbelt. But excessive logging is driving some species to the brink of extinction. BC’s Conservation Data Centre lists over 40 species at risk in the humid/wet forests of the Interior Wetbelt.

The park proposals below are urgently needed to protect rare remnants of ancient Inland Temperate Rainforest. This type of rainforest occurs nowhere else in the world but in the province of British Columbia (BC), Canada. Most of it occurs in southeastern BC, in a mountainous region known as the Interior Wetbelt. But excessive logging is driving some species to the brink of extinction. BC’s Conservation Data Centre lists over 40 species at risk in the humid/wet forests of the Interior Wetbelt.

The mountain caribou of this region have been assessed as genetically unique, endangered, and irreplaceable. Their historic occurrence in BC is synonymous with the Interior Wetbelt, and they are closely associated with the Inland Temperate Rainforest. Called “deep-snow mountain caribou”, they are the only caribou adapted to spending winters in deep snow, high in the subalpine of rugged mountains; but to survive they must seek lower-elevation forest the other half of the year. The remaining old-growth is critical to their survival. Scientists warn that they are in imminent danger of extinction due to excessive logging.

The park proposals below are designed to increase protection of these lower elevation old-growth forests. They are amongst the highest biodiversity forests in Canada, and one of the highest in carbon storage. These are proposals to expand and connect existing parks, but can this help the mountain caribou? Yes! Maps show that most of the core mountain caribou range in the central Interior Wetbelt today overlaps existing parks but is mostly outside the boundaries. This is because most of the low-elevation old-growth forest wanted by the logging industry was excluded when the parks were created. It is time to extend the boundaries to take in the critical caribou habitat.

Click here to learn more about the biodiversity of Inland Temperate Rainforest

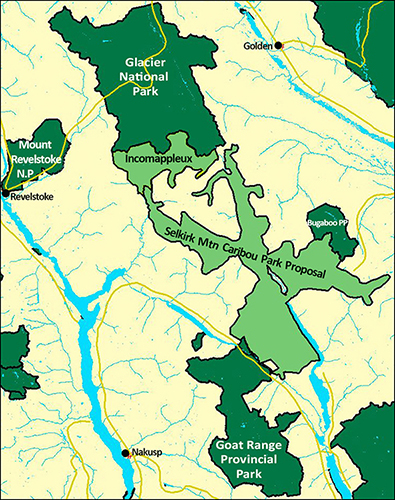

Selkirk Mountain Caribou Park Proposal

Click here to sign the Change.org petition to create this park proposal.

A mountain caribou bull of the Central Selkirk herd standing in or near the park proposal. The herd is severely endangered and has dropped from 98 to 28 animals since the park was first proposed. Logging in federally-designated critical matrix habitat for this herd is occurring in two locations, increasing danger to the herd. Photo by Karl Gfroerer.

Although it was named for its endangered mountain caribou, this park proposal would also provide critical connectivity and fishing locations for the survival of the resident grizzly bears. Sixty-six percent of the proposal is provincially designated Ungulate Winter Range for mountain caribou and largely off limits to logging, but this protection is partial and weak.

The park proposal includes a number of remnant old-growth forests, the greatest of which is in the Incomappleux Valley (shown above). Biologists believe this forest may have been growing continuously since the last Ice Age. The tree is an estimated 1,800 years old. Loaded with rainforest lichens, mushrooms and other small species, many of them rare, this forest has been called a Notre Dame of biodiversity. Logging this forest has been obstructed for years by protests, as well as expensive damage to the road by rockfalls and slides. Nevertheless, there are five approved cutblocks in it and the license holder, Interfor, could fix the road without informing the public if it chose to do so.

Two BC Auditor General reports have said that BC is not protecting biodiversity because parks are too few and too small. The park system needs to be expanded, and parks must be connected by protected travel corridors if grizzly bears and mountain caribou are going to survive.

This park proposal includes parts of four rivers to connect three existing parks. Despite considerable clearcutting along the rivers, these low-elevation riparian habitats have the highest biodiversity in these steep mountain valleys. They connect key stands of old-growth forest, and provide crucial food and travel corridors for large wildlife. The rivers are spawning habitat for blue-listed bull trout, kokanee salmon, and giant Gerrard rainbow trout of Kootenay Lake and the Lardeau River.

Upper Incomappleux River with Intact ancient rainforest outside Glacier N.P. Photo: C. Pettitt. The Selkirk park proposal would expand Glacier National Park to protect another 17 kilometres of the Incomappleux River that runs through a 27,364-hectare, completely intact wilderness. The forest is extremely rare, very wet primeval rainforest.

This wilderness has been identified in a federal government report as critical for the survival of the grizzly bears in the park. Biologists have said the park itself is too small, and fragmented by a highway and railroad, to maintain grizzly bears.

government report as critical for the survival of the grizzly bears in the park. Biologists have said the park itself is too small, and fragmented by a highway and railroad, to maintain grizzly bears.

There is a similar situation with the Goat Range Provincial Park to the south. (About one in ten of its grizzly bears have a whitish coloration and markings similar to Siamese cats.) However, like Glacier National Park, the majority of Goat Range Provincial Park is high elevation habitat. Like mountain caribou, grizzlies descend to the valley bottoms. In autumn they are attracted outside the boundaries of the park to fish for spawning Kokanee salmon. They also likely mix with the bears across the river, in the Badshot Range.

Grizzly bear populations to the south of the Central Selkirk Mountains have been shown to below, with the most southerly populations toward the U.S. border being a serious conservation concern. It is only at the latitude of this park proposal that grizzly bear population are more healthy, but scientists have warned that they will not stay that way unless they have sufficient connectivity of protected habitat over a large area. The Selkirk Mountain Caribou Park Proposal would provide the connectivity urged by BC’s Auditor General, and give the bears sufficient space to roam, find food and mates and stay safe from humans.

The grizzly bears shown here were photographed within or very near the boundaries of the Selkirk Mountain Caribou Park Proposal. Photos by Craig Pettitt.

Take action!

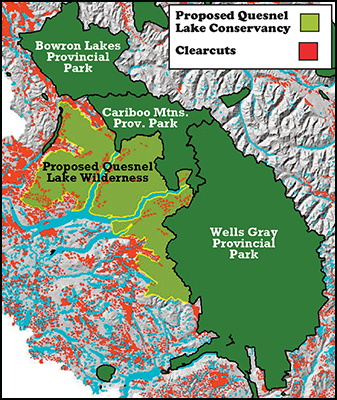

Quesnel Lake Wilderness Proposal

The proposed fully protected area surrounds the North and East arms of Quesnel Lake. It is an area of great significance to First Nations, endangered wildlife, and all British Columbians. As a major tributary to the Fraser River, it contributes to BC’s wild salmon stocks, including not only Sockeye salmon, but also endangered Coho salmon. Its forest is rare old-growth Inland Temperate Rainforest, critical to the survival of the Wells Gray North herd of endangered mountain caribou.

The proposed fully protected area surrounds the North and East arms of Quesnel Lake. It is an area of great significance to First Nations, endangered wildlife, and all British Columbians. As a major tributary to the Fraser River, it contributes to BC’s wild salmon stocks, including not only Sockeye salmon, but also endangered Coho salmon. Its forest is rare old-growth Inland Temperate Rainforest, critical to the survival of the Wells Gray North herd of endangered mountain caribou.

Rich with cultural heritage sites, the area is in the traditional territory of the T’exelc First Nation (Williams Lake Band) and the Xats’ull First Nation (Soda Creek Band). These are two of the four bands that make up the Secwepemc Nation.

This area is also prime grizzly bear habitat, and bears gather on sandy beaches to feed on a diversity of wild salmon and trout species. Quesnel Lake is very unique as it is thought to be the deepest fjord lake in the world. This proposal contains the largest intact body of old-growth Inland Temperate Rainforest currently known to exist. Its position adjacent to existing parks would give wildlife a larger intact wilderness.

Existing Mountain Caribou Protection is an Illusion

The Wells Gray North mountain caribou herd is one of the largest in existence, with an estimated 200 animals. The entire park proposal is federally-designated critical habitat for mountain caribou, and the Species at Risk Act says it should be protected. Unfortunately, Canada has done nothing on the ground to enforce this law. An agreement currently under consideration by BC and Canada would not stop the logging and would not protect the low-elevation old-growth forest needed by the caribou.

Despite some clearcutting along the lake, a strip of old-growth low-elevation forest has been left along the lake that is critical habitat for survival of the caribou. The population of the herd has been relatively stable, leading to hopes that there is enough forest left for them to survive.

The provincial government of British Columbia has designated about 50% of the park proposal as Wildlife Habitat Areas (WHAs) for mountain caribou. Unfortunately, a large amount of the WHAs allow some logging, in addition to past clearcutting before the WHAs were created. Logging more than 30-35% of a landscape kills mountain caribou by increasing predation and reducing their access to food. The WHAs also do not protect from mining, energy or tourism development.

The old-growth forest has trees that may be 500 years old or more. The salmon spawn along the lakeshore and die after spawning. Their remains fertilize the lake, producing giant rainbow trout and a fisherman’s paradise. Grizzly bears and bald eagles congregate to feed on the dead fish, carrying the remains into the forest and also leaving behind high-nitrogen droppings. This has fostered an explosion of lichen diversity. Scientists estimate there are hundreds of lichen species in this forest, many of which are associated with old-growth rainforest on the coast. In 2007 species of lichens new to science were found in the forest along Quesnel La ke, as well as rare species such as Nephroma occultum. For photographs and scientific information on Inland Temperate Rainforest click here. VWS is seeking full, permanent protection.

ke, as well as rare species such as Nephroma occultum. For photographs and scientific information on Inland Temperate Rainforest click here. VWS is seeking full, permanent protection.